By Nathan Hosler

This blog post is a sermon given by Office of Peacebuilding and Policy director Nathan Hosler. To learn more about Christian Peacemaker teams, visit their website here.

Luke 1:68-79

We are called to be a sign, a witness to the peace of Christ. To proclaim rightly, means that the peace of Christ cannot be forced. We can’t impose peace, at least not a true peace that is both geopolitical and personal, that is both an inward reconciliation and an outward wellbeing, that is both reconciliation to God and to neighbor and even, inexplicably, to our enemy. We cannot—nor should we try—to force peace. We bear witness to it, proclaim it. We must struggle for it—we must dedicate ourselves to it.

In our Luke passage there are two layers of proclamation. One is of the coming savior. In verse 68 we hear—“The Lord has redeemed”. In the next verse “He has raised up a mighty savior for us in the house of his servant David,..” This will be Jesus, Emmanuel—God with us. The Prince of Peace. This is the Advent waiting for the incarnate one. This is God coming near to heal.

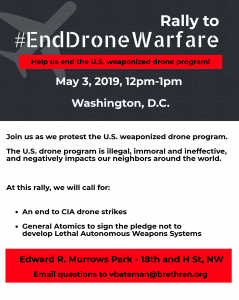

In a resolution on drone warfare initially drafted in the Office of Peacebuilding and Policy and then passed at our 2013 denominational Annual Conference—we referenced this coming near to heal. It reads in part:

All killing mocks the God who creates and gives life. Jesus, as the Word incarnate, came to dwell among us (John 1:14) in order to reconcile humanity to God and bring about peace and healing. In contrast, our government’s expanding use of armed drones distances the decisions to use lethal force from the communities in which these deadly strikes take place. We find the efforts of the United States to distance the act of killing from the site of violence to be in direct conflict to the witness of Christ Jesus

While our policies and practices often pull us apart, drive wedges between groups, and heighten animosity—our ministry of reconciliation and peacemaking is proclaimed by the one for whom we wait this advent.

There is also a second layer of proclamation in Zechariah’s song—that of the messenger, John—who will be called John the Baptizer. He will prepare the way for the Holy one. In verse 76 we read, “And you, child, will be called the prophet of the Most High; for you will go before the Lord to prepare his ways,…”

Throughout this text, through the two layers of proclamation we see the mighty acting of God on the plane of human history. The passages ends with— “By the tender mercy of our God, the dawn from on high will break upon us, to give light to those who sit in darkness and in the shadow of death, to guide our feet into the way of peace.”

To guide our feet into the way of peace. Because many of us have read the story beyond Christmas, we know that the awaited baby Jesus will become the teaching Jesus who will say, “Blessed are the peacemakers for they will be called the children of God.” He will teach to love one’s enemy and pray for the one that persecutes you. He will teach to go and confront and be reconciled. He will guide our feet into the way of peace.

In this town peacemaking is an odd word. Even for organizations that work for things that I would characterize as peace, peacemaking—the term—is a little unusual. While at dinner after speaking on a panel about Nigeria, I was talking with a colleague from one such organization. I was in the throes of dissertation writing and I revealed that I was writing on peacemaking within the work of Stanley Hauerwas. While she certainly didn’t know of Hauerwas she also wondered why the term peacemaking rather than the more common “peacebuilding.” I noted that while I use the terms somewhat interchangeably, the term peacemaking is based on the biblical text, “Blessed are the peacemakers for they will be called children of God.”

But why are these peacemakers called the children of God? A chapter later we read– Love your enemy because God who is your heavenly parent sends rain on both the righteous and unrighteous. God provides even for the enemy. To resemble your parent is to demonstrate that the you are a child. “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called the children of God.” I am not sure when I first learned about Christian Peacemaker Teams, but I think it was sometime as a child. I grew up in a Church of the Brethren congregation and my grandfather and his brothers were conscientious objectors. I grew up believing that to follow Jesus meant serving others and being against war. In college as my understanding of my vocational call to ministry took shape, I felt the same theological impulse that brought about CPT—If I am opposed to war, I need to be ready to work for peace. For my graduate work in international relations I almost wrote on Christian Peacemaker Teams.

I have a vivid memory of being at the Church of the Brethren’s Annual Conference over the time when I was beginning to decide what I would research. We met up with Art Gish, an old CPTer, to talk about intentional community. While walking briskly through the crowds of people I told him I was considering writing on the power leveraged by CPT as international actors. The picture caught in my mind is him looking back at me, with his bushy white brethren beard, a big smile and laughing, saying “I don’t know why it works, but it works!” The earlier work of CPT focused on “Getting in the Way,” more explicitly using their international presence in nonviolent resistance to both stop violence and highlight the situation for the broader international community. This then plays on international institutions, geopolitics, and broadly international relations—hence my interest as a Historic Peace Church kid studying international relations. While CPT still works in this context its work and framing of its work has evolved over the years. We now describe the work thusly: “CPT builds partnerships to transform violence and oppression.”

We then expand this by describing this short phrase by stating that the work is:

Inclusive, multi-faith, spiritually guided peacemaking. We approach injustice from a spirit of faith and compassion.

CPT accompanies and supports our partners in their local peacemaking work in situations of violent oppression.

Committed to undoing the structures of oppression that feed violence, both in society and within our organization.

Christian Peacemaker Teams has projects in Iraqi-Kurdistan accompanying human rights defenders and supporting communities being bombed, the city of Hebron in the West Bank of Palestine accompanying during things such as the olive harvest and monitoring heavily militarized checkpoints that children pass through on the way to school, Winnipeg, Canada with the Indigenous Peoples Solidarity Program, in Colombia with small holder farmers at risk of displacement from their land, and a regional project on the Island of Lesbos with arriving refugees.

First, CPT’s work is Inclusive, multi-faith, spiritually guided peacemaking. We approach injustice from a spirit of faith and compassion.

A few weeks ago, Marcos Knobloch, a full-time CPTer on the Colombia team, was with me DC. My office arranged a series of meetings with partners and US government bodies—specifically the Tom Lantos Commission on Human Rights staff and with the State Department. In the course of telling about their work he noted that while there are a number of international organizations working in their area of Colombia, CPT is the only one that is faith-based. This spiritually guided peacemaking gives them a particular pastoral work as they accompany people that have suffered violence.

Secondly, CPT accompanies and supports our partners in their local peacemaking work in situations of violent oppression.

Marcos also spoke about CPT Colombia’s work to protect human rights defenders and vulnerable communities. Since the signing of the peace accords late in 2016 there have been 350 assassinations—approximately 1 every other day. In this context CPT works with the Corporation for Humanitarian Action for Peace and Coexistence in Northeastern Antioquia (CAHUCOPANA). CAHUCOPANA has being working for human rights for small scale miners and farmers for 14 years and because of this work has faced many threats. CPT has been working with them since 2009. While the government has agreed to provide such leaders protection, this is often limited to cities. In these isolated areas accompaniment is vital. In this, CPT plays an unique and critical role.

Thirdly, CPT is Committed to undoing the structures of oppression that feed violence, both in society and within our organization. In Canada, with the Indigenous Peoples Solidarity project this involves working for decolonization and challenging corporate and government exploitation Indigenous nations. In Hebron this involves living and working in the old city—being a physical presence in a contested space and documenting the military occupation.

“CPT builds partnerships to transform violence and oppression.”

“By the tender mercy of our God, the dawn from on high will break upon us, to give light to those who sit in darkness and in the shadow of death, to guide our feet into the way of peace.”

In this second Sunday of Advent we continue to prepare for the coming of Jesus. The one who will embody peace, who will bring reconciliation and justice, and who will teach blessed are the peacemakers. The incarnation—the coming of Jesus—is the showing up of God to bring healing.

Show up. Peacemaking, like the Incarnation, involves showing up.

I invite you to continue with us in this important work. We need our teams on the ground. We need individuals to go on two-week delegations to learn, support, and then tell the story. We need funds, prayers, passing on our publications. As the Apostle Paul teaches in Romans–“For as in one body we have many members, and not all members have the same function.” (Romans 12). We are called to peacemaking. Our common call to peacemaking will look different. —may Christ guide us in the way of peace