A sermon at Washington City Church of the Brethren on May 3, 2015

By: Nathan Hosler

1 John 4:7-21

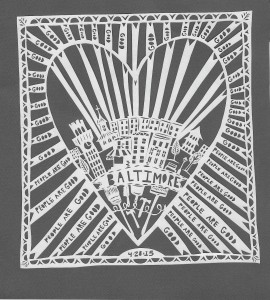

A week ago a nearby city was set aflame.

We likely felt many things during this time.

I was also reading for this sermon. Particularly reading and rereading the 1st John passage. Both these events and this passage require such depth of thought that I struggled to make sense and unpack all that needed to be considered. The passage was thick with theological considerations and the events contained layers hard to fathom. The passage begins:

“7Dear friends, let us love one another, for love comes from God. Everyone who loves has been born of God and knows God. 8Whoever does not love does not know God, because God is love.”

The potency of these words and the words that follow it are shocking when we pay attention and don’t read too quickly. Particularly how knowing and loving are connected in ways that we don’t typically connect.

Likewise the situation and discussions around race and police violence and community response require a depth of consideration that we may find hard to sustain. What is needed in such a situation? Is it to name the unnamed? To call out racism in our system—in ourselves? Should we try to “find out” what happened? Reading accounts and forming opinions on who did what and why and how? Do we need to form an opinion on what happened so we can choose a side, stake a position, argue a point? Does the world need me or us to say something, to add words to the cacophony, to argue for justice or truth or the institution or the oppressed community? Should we start with the text or the context? With God or the people?

It is in this situation that it is hard to know where to start.

This passage revolves around a particular, quite clear, and quite dramatic proposition.–

God is love.

What does it mean for God to be love? We typically say we love—which is a verb—that is we love someone or something. Or perhaps that someone—perhaps God—is loving, but in this we see “God is love.” If we back up just a verse and a half earlier we read the exhortation “Let us love one another.” This is predicated off of God as the source of love. It reads “for love comes from God.”

“7Dear friends, let us love one another, for love comes from God. Everyone who loves has been born of God and knows God.”

And it continues saying not only is God the source of love but those who love are born of God. The passage includes God being defined as love, being the source of love, noting how God demonstrates God’s love, how Jesus’ appearance is the embodying of love, and how we are also to be defined by love as children of God.

Whoever does not love does not know God, because God is love. 9 This is how God showed his love among us: He sent his one and only Son into the world that we might live through him.

That we might live through him.

This is how God showed his love among us: He sent his one and only Son into the world so that we might live through him. God’s love is demonstrated to us through the giving of life. It is not so much that life is the ultimate goal as that it is the concrete expression of God’s love toward us. As such it is not to be taken lightly. Life is not to be thrown away. However, life is not the ultimate goal. At least life as we tend to describe it. As I believe Shaine Claiborne has said, the goal of life is not to get out of life alive. Meaning that life is of great value but in order to live I need to give my life, and not take life or devalue other’s lives because they are a different race, nationality, political opinion, economic position, or sex.

Why are there so many deaths by police in the news recently? Is there an increase or is what has always happened just making it into the news? I recognize that I am a white man and as such feel both compelled to talk about racism and a little anxious. But I feel that I must at least attempt to speak.

I must admit I am unsure what to say. You have likely heard much talk of what happened and how people responded. You likely heard that though there were many strong responses to Freddie’s death these varied in how they were manifest on the street. You also heard people’s responses to these various actions and then heard other people criticizing certain leaders for calling people involved in destruction “thugs.” I was neither there nor am I an expert on all that was said or done. I, as such, don’t feel qualified to comment very specifically but do feel compelled to respond in some manner—at least give some reflect on how we as a church might respond. I am, of course, not assuming that our congregation or denomination is only white. This would further monopolize who is assumed to be “really” Brethren. I am also not assuming that everyone is either white or black as if those are the two binary options. Nor am I assuming that any of these groups are monolithic without cultural, political, theological, historical, or other differences. Though Brethren are not mono-ethnic or mono-culture it is critical to recognize that Brethren persons of color have often been marginalized and experienced racism and prejudice at Brethren events. The January edition of the Messenger magazine bears witness to this. So while this sermon is not attempting to comprehensively address race and racism in our church I felt these few notations were necessary.

In addition to preaching, I am also a doctoral student in theological ethics. One of the books on my shelf that I hadn’t gotten to reading yet was James Cone’s A Black Theology of Liberation. The book was first published in 1970 to provide an expanded theological reflection and foundation to the Black Power and Civil Rights movements. So while beginning to think toward preaching this Sunday in light of Baltimore I began reading this work. He begins asserting a basic presupposition that should guide the work of theologians. He writes,

“Theology can never be neutral or fail to take sides on issues related to the plight of the oppressed” (James Cone, “A Black Theology of Liberation: Twentieth Anniversary with Critical Responses,” Orbis Books, p4.)

As such, taking sides with the oppressed is the organizing principle rather than fairness. Because when fairness is the dominant approach the dominant will always come out on top. The dominant can control media and hold sway (or control) institutions. This does not however mean that truthfulness is abandoned but that our stance should be partial towards the oppressed. The default presumption is on the side of the oppressed. This is an expression of love as we have experienced in God.

Regarding Baltimore, when I hear claims of racism my default must be to presume that this is the case rather than my default being to question the claim. This means that my basic default is to trust such a claim rather than the counter claim of the system of the empowered and powerful.

“10This is love: not that we loved God, but that he loved us and sent his Son as an atoning sacrifice for our sins. 11Dear friends, since God so loved us, we also ought to love one another. 12No one has ever seen God; but if we love one another, God lives in us and his love is made complete in us.”

The logic and flow of this passage continues on quite clearly. God is love. God demonstrates love to us concretely through the coming of Jesus. Since we are in relation to God and God loved us we should love others. Even though we have not seen God we see God manifest and “made complete” when we demonstrate God living in us by loving on another. We also know that we know that we live in God because he has given his Spirit. Because of this we can rely on God and trust God’s love for us. We also can live without fear. We read:

“18There is no fear in love. But perfect love drives out fear, because fear has to do with punishment. The one who fears is not made perfect in love.”

There is of course the possibility that we get stuck here—with the loving and being loved by God and not fearing because we are relying on the love of God. It is, in fact, a good place to be. We do, however, have the tendency towards narcissism—the tendency to stop with ourselves as if we and our wellbeing are the end goal. This can even happen when we serve our church or our neighbor. It is hard to get outside ourselves. This is, of course, our primary reference point but it also can become our end point.

In these verses the love we experience originates in God and flows to us in Jesus and the Spirit but concretely presently manifest in those around us. We then love but as a response to first being loved. The passage reads,

“19We love because he first loved us. Whoever claims to love God yet hates a brother or sister is a liar. 20For whoever does not love their brother and sister, whom they have seen, cannot love God, whom they have not seen. 21And he has given us this command: Anyone who loves God must also love their brother and sister.”

So the love of God is manifest in those around us and must go out from us to our brother, sister, neighbor, and even those deemed our enemy. This is how we experience and show the love of God.

This love must seek justice. It must challenge racism in our communities and globally which prioritizes certain people over others. This love must also challenge the presumption that violence is ultimately effective by confronting the militarization of our police and foreign policy.

We must name what is unnamed.

Seek justice.

Embody love.

Amen

Appreciated your sermon. Living in Baltimore I am aware your comments are right on target. It has given me additional thoughts on the theme of “Love” that I can share with my friends and bible study classmates.

Love was the major topic in the most recent Brethren quarterly.

Thanks again for your words.